Buckle Up

Chapter 11- Día de los Muertos

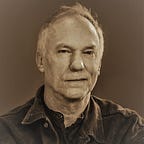

I’ve been thinking about Bruce because he had no illusions.

I would have stood at the prow of The Jolly Roger and fancied myself as Midshipman Horatio Hornblower scanning the horizon for vessels loaded with Spanish silver. Bruce would have dived into the water with a serrated dagger between his teeth and pretty soon we’d be sitting around the braai eating crocodile steaks while his lover swooned at his shoulder and fondled her newly-acquired bejewelled timepiece.

I thought life would be full of wonderful possibilities if only reasonable men and women could come together to arrange the affairs of the world with common sense and compassion. Bruce thought life was the pumping heart of a rabbit caught in a snare.

Bruce kept snakes as pets and squashed frogs with bricks. My heroes wrestled with giant anacondas in the Amazon forests.

The only thing that made Bruce squeamish was pretentiousness, which included anything that smacked of affectation in dress, manner, style, attitude or language, and the merest hint, in particular, of intellectual airs. I was squeamish about everything that wasn’t in a book.

Bruce despised pretentiousness so much that he wouldn’t use a word like pretentiousness to describe it.

Bruce despised pretentiousness so much that couldn’t forgive a classmate of his for pointing out, while they were walking along the banks of the Bushman’s River one Sunday afternoon, that the single-engine aeroplane crossing the sky above them had a “retractable undercarriage”. The incident stuck in my mind and stayed there because the ferocity of his contempt when he told me about it seemed so disproportionate to the offence.

I loved words, and the longer and the more obscure the better. I devoured the dictionary from aardvark to zymurgy. Each new word I came across seemed like a window into the secret world of adult thought, or a clue to the mysteries they were hiding from me. Quixotic led me to Cervantes. Cervantes led me to lewd. Lewd let me to lascivious. Lascivious led me to libidinous. Libidinous led me to carnal. The definition of carnal confirmed my worst suspicions about the hypocrisy of grown-ups.

I wondered why certain words existed if you weren’t allowed to use them.

I thought that if you could take all the words in the dictionary and arrange them in just the right order you would know everything there was to know.

I came across rodomontade in a Somerset Maugham short story and got reprimanded by my Standard Six English teacher for using it in a composition when the word grandiloquence would have served just as well. I was crushed. I wondered when, where and under what circumstances I would be allowed to be pretentious if it wasn’t in English Literature.

I loved words even after I’d learned that they were as unreliable as mouse-traps and as dangerous as double-edged swords, but then I loved them the way little boys love weapons.

But when I was around Bruce I watched my language.

His scorn for boys who used words like “retractable undercarriage” extended to boys who collected stamps or birds’ eggs or butterflies, to boys who knew the names and makes of cars, and to boys who read books involving childhood memories, the coming of age, or par-boiled sociological reflections — books, in short, like this.

The same judgements didn’t apply to girls. Girls could say anything, do anything and get away with anything. He worshipped girls, for better and for worse.

Bruce so hated the pretentiousness of his lecturers and fellow students at the Architecture Faculty of the University of Natal in Durban that he moved as soon as he had graduated to Newcastle in the north of the province, bought a yellow Valiant Charger with black racing stripes on the bonnet, and got a dog called Susie. His first commission was a recreation hall for the Dutch Reformed Church.

When we were away at boarding school at Merchiston and Estcourt he wouldn’t acknowledge my existence. He was three years ahead of me, and as distant as the gods are from ants.

But at home during the holidays, at New Dell and later at Drakesleigh, I was his faithful disciple and his obedient helper. I fetched things and carried things. I held things, I measured things, and I counted things. I waited for things to fetch and carry and hold and measure and count. I passed him things when he needed things. I did everything that didn’t require some craft or calculation. He invented, I watched; he led, I followed.

And throughout that time when we were in our teens, sharing a bedroom together and growing up together, I was always only a single misplaced step, a single mistimed movement of the hand, and a single ill-judged word away from his displeasure and my consequent disgrace.

While other boys were assembling model aeroplanes, Bruce was assembling skeletons.

My duty on the first day of every holiday was to collect the equipment and provisions required for the exhumation of corpses while Bruce studied the map which marked in crosses the places where we had buried them last Easter or last Christmas. I say “we” only because I was present at the internments, either handing Bruce the spade or throwing up in the veld nearby.

The crosses on the map were annotated with the date of burial and the type of corpse; so, for example: Small Sheep, Michaelmas, 63; or Porcupine, July, 64. The size of the animal and the date of burial provided a rough guide to the present state of decomposition. We started with the most likely first, hoping for bones relatively clean of messy flesh and stubborn cartilage, working backwards from there, if necessary, until we found a more promising candidate.

I wanted to imagine we were a team of explorers, like Burton and Speke searching for the source of the Nile, or Mason and Dixon setting off from Delaware to map the land of the Iroquios. But he walked ahead like Livingstone through the jungle, and I traipsed behind him like a native porter.

These expeditions took us from the familiar territories of the forests and pastures that surrounded the farmhouse to the furthest reaches of New Dell’s 2,000 acre universe; to the western border where the old railway line disappeared into a tunnel infested with bats and skittish creatures with cat-like eyes glinting the dark; through the Bunga-Bunga Jungle and up the northern slopes to the beacon that overlooked the fabled Lowlands in the hazy distance; and, to the east, beyond the Top Dam, to the great tracts of veld that ended suddenly and arbitrarily with the barbed-wire fence that demarcated the outer limit of the known world. The Emmanuels were said to live in that far blue yonder, like nomads, I thought, from the Israel of the Bible.

We looked for the stone cairns we had placed above the graves. Sometimes they’d been found by jackals or civets or stray dogs, and broken and useless bones would be scattered around the perimeter of the crime. Sometimes the skin or the hide of the dead beast would still be clinging fast to the rotting flesh, and the corpse would have to be reinterred for future inspection.

Specimens were deemed suitable if the shape of the skeleton was undisturbed and the worst of the rotting stink was over. Then the carcass would be placed very carefully onto a stretch of hessian sacking, rolled up into a neat bundle, and draped across my shoulders for the long trudge home.

I was relieved when he decided that the only part of the horse that was worth disinterring was the skull.

I did the drudge work of lugging, hauling, running backwards and forwards between the shed and the farmhouse, and fetching the hosepipe. Bruce did the dirty work of digging out with a pen knife the partially decomposed strings of muscle and bits of cartilage that clung to hip joints and shoulder blades, and the grisly business of scraping and cleaning decaying flesh from fragile bones. He wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

The most difficult part of my task wasn’t the stink of it or the slimy feel of filmy membranes and mucus. It was remembering where each bone he handed me belonged in relation to the next as I placed them on the green tarpaulin we had stretched out on a grassy patch behind the shed. One rib bone looked pretty much like another rib bone. I couldn’t tell an ulna from a radius. But Bruce would know when he began fixing them together with wire and string and rubber bands, because soon he would see from the shape of the skeleton that something was wrong, and the fault would be down to my damn cack-handedness.

In the end it proved too difficult to hang the finished skeletons from our bedroom ceiling without having their fibias and tibias and the smaller bits and pieces of the other bones collapsing into a tangled mess of string and wire and phalanges and fibulas. But he was happy to settle for a simpler concept, which involved dangling only the wire-threaded vertebrae and a few of the bigger bones from the skull, because he had read a story about aliens who bit humans on the back of their necks and sucked the fluid out of their spines to turn them into the living dead. He put the horse’s skull on top of the wardrobe as if to watch over his jiggling dance of the death.

I made a twin-fuselage Mosquito and hung it on our bedroom ceiling at an angle that suggested it was firing its machine-guns at the Stuka that was attacking my Lancaster bomber. I carefully avoided saying “twin-fuselage”.

I still have dreams of giant fleshless dassies knocking out squadrons of Spitfires and Hurricanes over the English Channel and causing us to lose the war.

Before he discovered The Agony and the Ecstasy, Bruce’s favourite book was Long Pig by a certain Russel Foreman. He read selected passages to me by the light of the candle next to his bed. To test Foreman’s theory that human flesh tasted exactly like pig flesh, Bruce made me tear bits of skin off my fingers, cook them on the electric heater until they were brown and crispy, and savour them as slowly as possible. He was right.

I pretended listen to Long Pig by drawing the blankets over my head so he couldn’t see that I was holding my breath and reading something pretentious by torchlight in the cave between my raised knees.

I put his fascination with the macabre down to his contrariness. That was the word my mother used to describe behaviour she tolerated but didn’t approve of. Helen was contrary when she threw one of her famous tantrums. As far as I knew, Rodney and Debby were never contrary. I was contrary when I sulked, which was more often than I care to remember. By the time Andy came along we had used up all the manners of contrariness, so he could do as he pleased. Behaviour that couldn’t be excused by contrariness she called objectionable. None of us wanted to be objectionable.

So I thought it was out of contrariness that he gave me heart-stopping frights in the dark passage that led to our bedroom, and scared me witless with stories of vengeful ghouls with bloody teeth and gleaming axes stalking through the Bunga-Bunga Jungle to kill us in our beds as the skulls and bones above me twisted slowly in the moonlight.

Many years later in Mexico City, where the fascination with death predates the Aztecs, I had the fanciful notion that Bruce would have felt at home there. He could have made the crazily coloured paper skeletons that decorated the graves on the Dia de los Muertos. He would have got drunk on the atole and mutilated the songs of the mariachis until sunrise. He would have picked a fight and feigned contrition and smiled his lop-sided smile and made a life-long friend and charmed the muchachas and eaten the most churros and laughed the loudest at the blackest humour of the thronging cemeteries.

I thought then that he had celebrated death the way the Mexicans did, as if the worship of it stood for everything that wasn’t available to them in their mortal existence.

But it wasn’t like that. He wanted to tear death to pieces with his bare hands. He wanted to know the whole gory truth of it before he gripped it by the throat and squeezed every last ounce of life from it.